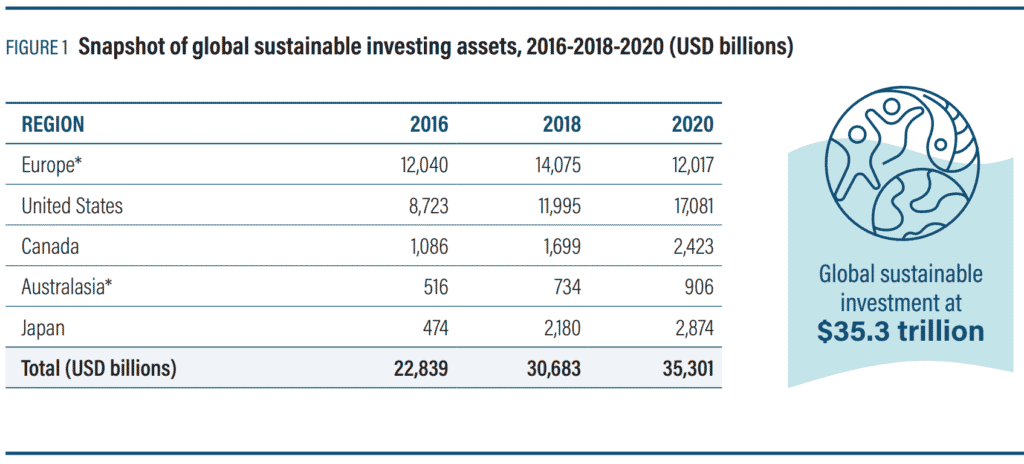

The Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (GSIA) reported an increase in global sustainable investments of 15 percent between 2018 and 2020, for a total of more than $35 trillion assets under management. That represented over 35.9 percent of all professionally managed assets under management reported worldwide.

The GSIA defines “sustainable investments” as investment approaches that considers environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors in portfolio selection and management. The organization points out that their definition is rather “inclusive” and also considers various ESG integration strategies.

The seven approaches considered by the GSIA are:

1) ESG integration;

2) Corporate engagement & shareholder action;

3) Norms-based screening;

4) Negative/exclusionary screening;

5) Best-in-class/positive screening;

6) Sustainability themed/thematic investing; and

7) Impact investing.

None of these approaches are mutually exclusive and, in practice, the proliferation of funds and strategies accompanying the growing demand are often mixed in different combinations in any one particular strategy. To add to this confusion, there are variations in the use and meaning of all these terms.

In general, the major broad umbrella industry terms used by professional investors when speaking about sustainable and responsible investing are the following:

1) Socially Responsible Investing (SRI);

2) Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG); and

3) Impact Investing

Each of these has its own specific characteristics and applications.

OK, so what’s the difference?

Different Terms, Same Difference

SRI, ESG, and Impact Investing have distinct differences in their social and environmental goals, while at the same time all of them incorporate traditional financial as well as non-financial criteria into the investment selection process. The range is wide: most ESG integration strategies just consider certain social and environmental criteria while other products have a key focus on creating a positive impact. Whatever the objective may be, a nuanced understanding of the terms SRI, ESG, and Impact Investing is helpful for educating yourself and realizing successful and rewarding outcomes.

SRI – The Granddaddy of Them All

SRI is one of the oldest and most recognizable acronyms in responsible investing and is increasingly used as umbrella, catch-all term covering all forms of sustainable & responsible investing (as we do on this site for efficacy reasons, and I did the same in my book, Sustainable & Responsible Investing 360º: Lessons Learned From World Class Investors). But historically it referred to Socially Responsible Investment primarily focused on negative screening, or intentionally not investing in certain types of companies (usually via public equities).

SRI strategy historically focused on socially relevant topics such as tobacco, arms, or gambling. But Patrick Drum, whom I recently interviewed, believes that the true origins of SRI date back to the tenets of Shari’ah law, established in the 7th century, because it has always been based on aligning investments with a values approach and Shari’ah compliant investments have similar exclusion screens to many SRI strategies. Drum, the leader of Environmental, Social and Governance investment research at Saturna Capital, also manages the Amana Participation Fund. That is the oldest and largest family of funds in the U.S. that strictly adheres to the principles of Islamic finance.

An SRI approach was also promoted in the 1700s by both the Quakers and John Wesley, the founder of Methodism – who advocated against investing in so-called “sin industries” like gambling. The Quakers also took an exclusionary approach to investing by actively refused to participate in the slave trade. Disinvestment in South Africa in the 1980s because of the country’s enforcement of Apartheid is yet another example. The most vivid example in recent history is that many SRI investors quickly divested themselves of holdings tied to Russia, when it invaded Ukraine in an unprovoked war.

ESG – It’s About the “How”

The term ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) is a newer term dating back to the early 2000s during the time when the Kyoto Protocol was being adopted, the Enron accounting scandal was discovered and the Exxon Valdez Oil spill occurred. Suddenly, the term SRI, which focused primarily on the “social” component didn’t seem to be comprehensive enough to include all aspects of responsible investing and the ESG investment strategy was born.

As early as 2004 / 2005, the international law firm Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer was commissioned by the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative to assess if ESG factors could be considered under the fiduciary responsibility of institutional investors when making investment decisions. Their report concluded that it was permissible and, arguably part of their fiduciary responsibility to do so. ESG assessments at the time were then seen as an additional risk management consideration and a potential value setting tool if requested by clients.

ESG investments integrate environmental, social, and governance principles and criteria into the investment decision-making process, alongside financial criteria. As Eric Rice of Blackrock puts it, “ESG is about how companies operate ─ treating society, the environment, and thinking about their governance in constructive ways.”

Examples of ESG metrics:

Environmental

- Climate change and carbon emissions

- Air and water pollution

- Energy efficiency

- Biodiversity and forest management

Social

- Gender and diversity

- Human rights

- Workforce relations

- Community relations

Governance

- Transparency, disclosure, and reporting

- Executive compensation

- Political lobbying

- Bribery and corruption

Harvard Business Review cited the example of IKEA, which introduced product, service, and process innovations to prolong the life cycle of materials it uses to make its products, and IKEA’s entrance into the home solar business.

Many ESG goals are also interrelated and therefore inseparable. An intriguing example was provided by Sharon Vosmek, CEO of Astia who explained to me that the United Nations found that if a company does nothing except successfully achieve gender inclusion, it positively impacts the UN’s other stated SDG goals. While the reporting of ESG measures is not mandatory in most jurisdictions yet, within the past several years more and more companies are providing such disclosures – due to the popularity and growing demand for ESG investment products.

Impact Investing – It’s about the “What”

While ESG refers to “how” businesses operate, Impact Investing is truly focused on the positive impact the invested money creates and can be thought about more in terms of “what” problems a business solves. An investor’s approach to impact investing will vary widely based on their goals, their objectives, and their organization’s capabilities, but to be considered an impact investor, they need to adhere to the Global Impact Investing Network’s (GIIN) Core Characteristics of Impact Investing (see Strategy Toolbox below).

Aiming for more transparency, the European Union has also developed a definition of what classifies an investment as an impact product as part of its Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR). The SFDR differentiates between:

- Article 6, products that consider sustainability risks,

- Article 8, products that promote certain environmental or social characteristics, and

- Article 9, products that have a positive impact on society/environment and key sustainability objectives as the core feature of their strategy.

Some examples of impact investors include Root Capital which is a nonprofit institution financing agricultural enterprises in Africa and Latin America. One of those enterprises is the Savannah Fruits Company in Ghana, which produces shea butter for export and provides rural women with access to a well-paying market for shea nuts. By removing barriers to cash flow, Root Capital enables Savannah Fruits to scale up – while paying the company’s suppliers above-market prices.

The Lok Capital fund invests in the Drishti-Eye Centre in India, where 80 percent of blindness could be avoided with proper diagnosis and treatment. Drishti-Eye Centre, via hospitals, vision centers, and mobile eye clinics, can reach patients who previously have not had access to quality eye care.

Another Impact Investor is the Lundin Foundation, which helps fund small and medium-sized businesses in sub-Saharan Africa – such as Rent-to-Own Limited Zambia. This agricultural equipment leasing company creates access and technical expertise in locales where equipment retailers, market information, and financing options are either limited or non-existent – supporting farmers, boosting local job markets, and stimulating the agricultural economy.

The Strategy Toolbox

There are five primary approaches used by investors to measure and bring about positive change in SRI, ESG and Impact Investing:

- Negative Screening – Negative screening refers to weeding out investments based on personal values. For example, investors may want to avoid companies who make money from firearms, tobacco, or partnerships within dictatorial regimes that engage in human rights violations. Exclusionary screening is a similar term, which means removing assets that contradict one’s ethical standards from an investment portfolio.

- Positive Screening – Positive screening is showing an investment preference for companies with better or improving SRI/ESG performance relative to their competitors or peers within their sector. For example, in my interview with Amy Novogratz, Co-Founder of Aqua-Spark, she explains how they invest in companies developing a sustainable, optimal aquaculture food system all along the aquaculture value chain. Investing in preferred companies often results in lowering their cost of capital.

- Active Ownership – Active ownership is the practice of engaging with companies on SRI/ESG issues to effect measurable change. This approach is in contrast to the strategy of divesting from ownership or “voting with your feet” by abandoning ownership. Threadneedle’s Simon Bond explained to me that he will often engage with such controversial companies if he thinks they are willing to move in the right direction. He will ask tough questions and demand accountability in a way that engages them and motivates them to make positive changes.

- ESG Integration – ESG integration involves the incorporation of environmental, social, and governance concerns into a predefined investment strategy that may involve some or all of these approaches. Trillium Asset Management’s Matt Patsky described to me an example of this approach applied to the environmentally fragile Chiapas region of Mexico. When it was provided resources such as technical expertise, loan capital, and access to markets, the community’s income increased five-fold.

- Impact Investing – According to the GIIN’s Core Characteristics of Impact Investing published in 2019, impact investments must have four primary characteristics:

- Intentionality – Investors must intend to have a positive social and/or environmental impact,

- Investment with return expectations – investments are expected to generate a financial return on capital,

- Impact measurement – they manage investments toward the intended impact by establishing feedback loops and communication of social and environmental performance ensuring transparency and accountability, and

- Range of return expectations and assets classes – returns can range from concessionary to risk-adjusted market rate and across multiple assets classes.

SunFunder, for example, raises funds for solar energy projects in Africa and Asia, to help improve access to clean energy. These investments mitigate 750,000 tons of C02 emissions per year.

Turner Impact Capital focuses its impact investments on affordable housing and tenant satisfaction.

The EcoEnterprises Fund invests in companies pioneering biodiversity by working with local communities or creating value through innovation within that space. They invest in the Columbia-based company Ecoflora Cares, for example, which works with local communities under the UN Convention for Biodiversity to produce a natural colorant for foods.

Weaving Together the Common Threads

SRI, ESG, and Impact Investing each have their own characteristic differences. Depending on what sustainable and responsible investment strategy you are considering, some of them might be best suited for investors with a patient vision and longer-term horizons, who measure value with a yardstick of more than just monetary gains. They inspire and instigate welcome and future-forward changes in how corporations and financial systems operate. They advocate for greater transparency and inclusivity. They make powerful, measurable contributions to sustainability, and to the greater good for society at large.

Don’t Leave Impactful Value on the Table

Matt Patsky of Trillium Asset Management told me that, “If you aren’t including environmental, social, and governance factors in your investment process, I am firmly of the belief that you are in violation of your fiduciary duty. You’re losing value and you’re also firmly separating any concept of having responsibility for the impact of money. You’ve thrown that out the window.”

Other leaders in the SRI space have expressed the same viewpoint, and it is important to note that Millennial investors, who represent the future, tend to agree. A recent deVere Group survey reported that 77 percent of them consider ESG issues a top priority, when evaluating their investments.

I’ve tried to clarify here in broad brush strokes the main differences between SRI, ESG, and Impact Investing which are the primary investment ‘buckets’ investors use to describe strategies they are using to invest for impact and positive change. As responsible investing is continually evolving, how investors actually execute/implement their strategies will vary depending on the type of asset class and the investor’s objectives.

Learn More About SRI, ESG & Impact Investing

To learn more about how professionals are actually implementing these strategies in the marketplace today with investor capital, you can read my interviews with many of the experts I’ve referenced in this article and many others in my book ‘Sustainable & Responsible Investing 360°: Lessons Learned From World Class Investors’. The book contains 26 interviews with leading, world-class SRI investors, and you can obtain your copy here. You can find a complete Table of Contents and read the full Introduction and excerpts from the first chapter and my interview with Jed Emerson of Tiedemann Advisors for free here.

You can find out more by listening to the complete interviews of these investors on the SRI 360° Podcast. In each episode, I interview a world-class investor who is an accomplished practitioner from all of the major asset classes. In these interviews, I cover everything from their early personal journeys—and what motivated and attracted them to commit their life energy to SRI—to insights on how they developed and executed their investment strategies and what challenges they face today. Each episode is a chance to go way below the surface with these impressive people and gain additional insights and useful lessons from professional investors.

To listen to any of the past episodes for free, check out this page. You can also subscribe and listen on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, RSS feed, Overcast, Podcast Addict, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, Castbox, Google Podcasts, Amazon Music or on your preferred platform for listening to podcasts.